Tag Archives: prison literacy

How 1 Man Spent 10 Years Behind Bars

“Days in prison have a sameness to them, and my most meaningful and frequent conversations were with authors.” –Daniel Genis

An interesting post on The New Yorker details the author’s conversation with a man, Daniel Genis, recently released from prison. The article mostly discusses what Genis did during his 10 years and 3 months in prison: read. It appears Genis read everything he could get his hands on from classics to the more obscure–for example–books on sumo wrestling and sausages.

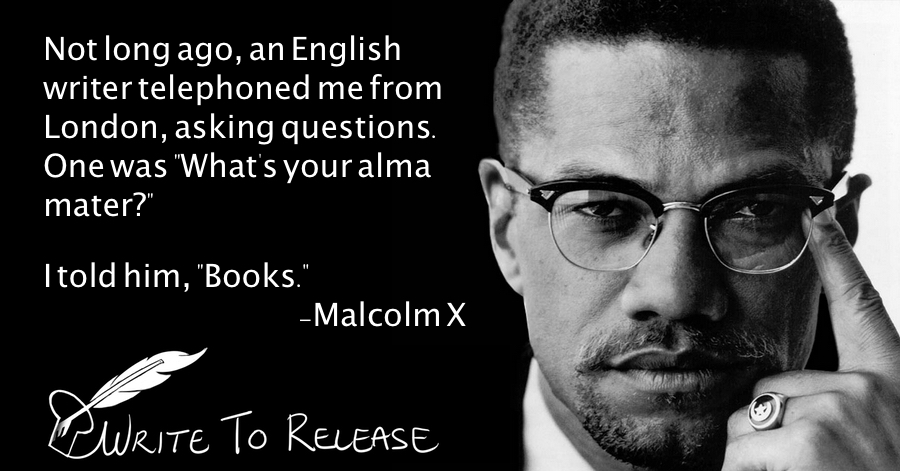

While incarcerated, Genis kept a journal documenting all the books he read with commentary provided for each entry. He notes that he “started out with books that helped me make sense of the situation around me.” These titles included The House of the Dead by Fyodor Dostoevsky and The Autobiography of Malcolm x. He obtained his books from his father, prison libraries, or ordered from catalogs.

Genis speaks of not wasting time in prison because that virtually wastes your life. Instead, he says that reading Proust instilled in him the need to write in order to exist outside of prison. To that end, Genis completed a novel while incarcerated.

Find out more of what Genis read while incarcerated by reading the article here.

Thursday Thoughts

“Writing is a form of personal freedom. It frees us from the mass identity we see in the making all around us. In the end, writers will write not to be outlaw heroes of some underculture but mainly to save themselves, to survive as individuals.”

2Pac – “Sometimes I Cry”

In class at the Lake County Jail we have read a diverse selection of works that have generated insightful conversation and proved helpful in modeling various writing forms. Most recently, a student mentioned that Tupac Shakur–primarily known to me as a (great) rapper–had written a good deal of poetry. Keeping with our efforts to expose the students to a wide range of voices, I got my hands on his posthumously-released poetry collection The Rose that Grew from Concrete and brought some of the poems to class.

Last week we read and discussed “Sometimes I Cry” (printed below). It elicited some powerful discussion on imposed gender roles and the expectations they carry, how we can help one another, and how to gather strength when one feels broken.

The moment was also important as it reinforced the fact that in that small, concrete-lined, poorly-lit room we all have the ability to learn from one another.

Sometimes I Cry

I cry because I’m on my own

The tears I cry R bitter and warm

They flow with life but take no form

I cry because my heart is torn

and I find it difficult to carry on If I had an ear 2 confide in

I would cry among my treasured friend

But who do you know that stops that long

to help another carry on The world moves fast and it would rather pass u by

than 2 stop and c what makes u cry

It’s painful and sad and sometimes I cry

and no one cares about why.

–2Pac

A Prisoner’s Closest Friend…Is a Book

I was in prison for 16 years and seven months. Even on my most difficult days, books were my companions. Books were what inspired me to banish the feelings of vengeance from my heart, to struggle to survive. Books, and the joy that comes from writing books, brought me out of prison alive. –Mamadali Makhmudov

The title of this post and the aforementioned quote are excerpted from a moving piece recently posted on the English PEN website. English PEN is a UK based organization that seeks to “defend writers and readers in the UK and around the world whose human right to freedom of expression is at risk.” Their ongoing Books for Prisoners campaign highlights the thoughts of detained writers they have supported through the mission of their organization. Books for Prisoners asks its writers to speak to the importance of books and reading while incarcerated. I encourage you to read the piece in its entirety for Makhmudov’s candid explanation on what books meant to him as a prisoner.

An interesting part, which struck me, is his assertion that roughly 10% of the Uzbekistani prisoners he encountered spent their time reading. What Makhmudov does not make clear is whether this is an issue of access, interest, or a combination of both. What is important to note, though, is that the 90%, as characterized by Makhmudov, have little to live for. He states: “they have never read a book that awakens in them any hope for life, any love for their home, any hope for the future. Therein lies the whole tragedy.”

A tragedy may be an understatement, especially if this issue is access to books. While I don’t want to opine here on the reason, it is clear–given the work of English PEN and mention in an earlier blog post of the UK ban on sending books to prisoners–that prisoner access to books is an issue. Whether it is in central Asia, the UK, or here at home in Illinois (where some students recently told me they weren’t able to go to the jail library for 3 weeks), access to books should be a fundamental right of inmates, especially if we aim for the humanistic approach of rehabilitation. You don’t have to read stories like Makhmudov to believe that; you just have to imagine, for one moment, where you would be if you had never read a book.